When someone asks, “What sort of music do you like?” I tend to fumble and search for a way to say, “A bit of everything,” without sounding completely vapid. The cliche is a bit of everything except rap and country (which has implications that are a whole different discussion); I never ruled out rap or country, but for a while, I could at least append, “except opera.” It struck me a bit the way ballet does—it’s hard for me to ignore, while listening to it, the fact that there’s supposed to be a larger performance at play. By fluke, I ended up with a dancer friend, and so I ended up at the ballet, and so I cultivated the ability to hold the performance in my head while listening to the music (or else to watch every “Trepak” video on YouTube) but I never had that exposure to opera. Then COVID happened, and a singer friend shared broadcasts from opera folks trying to adapt to the distance, and, well, now I need to come up with something else to exclude.

I want to have an exclusion because I don’t want to give the impression that I like everything. It’s not that I’m not picky, just that my criteria are eclectic, often arbitrary, and rarely connected to any of the labels we use to group things. I think I’ve finally come up with a name for it, though. Let me give it a try and see how it feels.

Hey, Alice, what’s your favorite type of music?

It’s called the all-nighter.

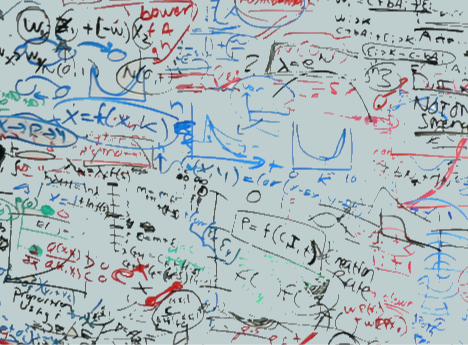

Imagine this: You’re on a creative development team. You were given a week to come up with the Next Big Thing, and now here you are, the day before your big meeting to give the pitch, and you have wastebaskets full of idea maps, brainstorming charts, half-drafted concepts … but no finished product. Most people have headed home for the day, but your team has come to the unspoken agreement that you’ll be staying late. Someone makes a coffee run. You order pizza and continue talking through ideas. Your whiteboard markers are drying out; you’re making a list of themes in yellow when someone else makes a Red Bull run.

Around midnight, you hit a slump. Your meeting is in nine hours. What’s the point? You have nothing; you may as well just go in there and own up to it.

How nihilistic, someone remarks, snapping the pop tab off their long-empty Red Bull. The Next Big Thing is … wait for it … nothing.

There is dejected laughter that dies out into dejected silence, but then something in the mood shifts. Because what if …

The all-nighter is whatever follows that what-if. What if it’s Metallica … but with cellos? What if it’s country, but we replace the F150 and moonshine … with a 747 and mini bottles? What if it’s … whatever this is?

Here’s the other thing about your hypothetical creative development team. The company you work for? They’re understaffed. (Maybe part of the reason it’s 4am on the day of the meeting before you have your pitch ready is that you’ve all been busy doing three jobs?) The all-nighter isn’t just about having a twist; it’s about having a reckless twist, the sort of absurdity that can only flourish under a false sense of invincibility fueled by caffeine, sleep deprivation, and the realization that, well, what are they going to do—fire you?

The all-nighter isn’t a genre just of music. There are all-nighter books, movies, podcasts; there are arguably all-nighter dishes, tea blends, single-batch sour ales that deserve a rerun, if only so I have a chance to stockpile. And, like most things that happen after hours, it’s not always good—part of recklessness, after all, is the higher-than-average chance of a fiery crash-and-burn disaster. I don’t know what makes a given all-nighter successful; all I know is that my new favorite cover is by Like A Storm, which is describes itself as “an Alternative Metal/Rock band from New Zealand, best known for blending heavy riffs with the DIDGERIDOO”:

… and if that doesn’t exemplify 4am pseudo-hypomania, I don’t know what does.

It’s a cliché, the insomniac writer, cursed with consciousness in the lonely, no-man’s-land hours after closing time and before the coffee shops have started their first pots. Maybe their haggard faces are lit by the glow of a computer screen; maybe they’re holding a half-drained bottle of gin in; maybe they’re lying spread-eagled in bed, staring at the ceiling, tired of counting sheep.

It’s a cliché, the insomniac writer, cursed with consciousness in the lonely, no-man’s-land hours after closing time and before the coffee shops have started their first pots. Maybe their haggard faces are lit by the glow of a computer screen; maybe they’re holding a half-drained bottle of gin in; maybe they’re lying spread-eagled in bed, staring at the ceiling, tired of counting sheep.