A disclaimer: This post brushes up against some big topics under the umbrella of LGBTQ+ concerns, and I am not going to do anything resembling justice to those topics. Good resources are out there if you’re looking to expand your appreciation for experiences outside the heteronormative; this post is not one of them.

Here are three things you should know about me before we go any further:

1. I love bad puns.

2. I am not a skilled archer.

3. But I am an aroace.

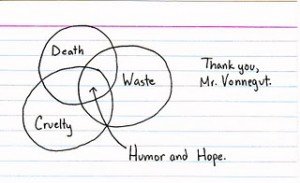

I grapple sometimes with the sense that I am defined less by my shape than by the negative space around me. I’m not a thing; I am an a-thing: an atheist, mildly anarchic, too apathetic to do much about it. And, in this month of Pride, an aromantic asexual.

Like bad puns, bad writing transcends gender, age, religion, political affiliation, race, and every other boundary we use to try to define our unique human shapes. Still, a corner of the internet has evolved to celebrate one overlap in the Venn diagram of poor prose: men writing women. Sometimes humorous, sometimes uncomfortable, sometimes calling into question the US educational system, but always betraying some fundamental misunderstanding of the Female Experience.

As fiction writers, we can’t be bound too tightly by a literal interpretation of write what you know. Still, there are considerations for writing what you don’t know, most of which involve remembering what assuming makes of u—and me, when I laugh at your expense. Which I do, shamelessly, even though I sympathize with those male authors whose writing is excerpted for its ridiculous shortcomings. We all have blind spots, those places to us so foreign we don’t realize how unknown they are until we try to capture them and discover (sometimes too late, courtesy of Reddit) how clueless we really are. Some people happen to be men; I happen to be aroace.

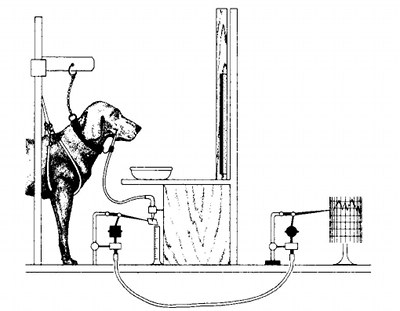

Let me say, for the record, that I have tried. In college, I was a few biology courses away from a minor in human sexuality. I’ve read studies and theories and analyses; for years, my go-to diversion in social situations was to discuss the erotic plasticity of female goats. (In short: Take a female baby goat and raise her with sheep, then introduce her to other goats as an adult, and she’ll mate with goats and sheep; take a male baby goat and raise him with sheep, and he’ll only mate with sheep even after being introduced to other goats.) At the risk of being uncouth, I’ll just say that I went well out of my way to make sense of sex—in large part because I wanted to be able to write it competently. Now, I understand it enough that I can fictionalize the drive for it the same way I can write about characters who enjoy recreational runs or big parties. Seems kind of sweaty, awkward, and inefficient to me, but hey—live your life. You do you, or your partner, or yours partners, so long as there’s informed consent all around.

Let me say, for the record, that I have tried. In college, I was a few biology courses away from a minor in human sexuality. I’ve read studies and theories and analyses; for years, my go-to diversion in social situations was to discuss the erotic plasticity of female goats. (In short: Take a female baby goat and raise her with sheep, then introduce her to other goats as an adult, and she’ll mate with goats and sheep; take a male baby goat and raise him with sheep, and he’ll only mate with sheep even after being introduced to other goats.) At the risk of being uncouth, I’ll just say that I went well out of my way to make sense of sex—in large part because I wanted to be able to write it competently. Now, I understand it enough that I can fictionalize the drive for it the same way I can write about characters who enjoy recreational runs or big parties. Seems kind of sweaty, awkward, and inefficient to me, but hey—live your life. You do you, or your partner, or yours partners, so long as there’s informed consent all around.

But then there’s romance. Deep down, part of me suspects romance is a myth, likely fabricate by Hallmark/the government/aliens/the Illuminati. I get emotional intimacy, bonding, attachment, and I get physical intimacy, closeness, affection—all that makes sense. But the idea that what we think of as a Normal Couple is anything other than close friends who also have sex—that there’s some mystical other component called “romance”? Seems a bit Emperor’s New Clothes to me.

In writing, I used to fade to black (or, I guess cut to white) whenever it was time for any sort of sexual activity. Now, I’m no master of erotica, but I like to think I can pull off a typical suggestive-but-not-explicit encounter. Romance, though? It all happens off screen. Take some characters; make them friends; make them get physical; yadda yadda the mysterious part … and bam, now they’re doing Romance.

Deeper down than my skepticism, though, is my fear that maybe some hurdles are too significant. Sure, I can conceptualize the mindset of a serial killer who believes they’re taking an ethically-sound approach to righting societal wrongs, but a character experiencing the development of a romantic relationship? No thanks. I don’t have the emotional fortitude to become a meme.

Writers are a crazy lot. It’s just something we assume, and

Writers are a crazy lot. It’s just something we assume, and  We all know

We all know