It’s that time of year. AWP 2015 has arrived; I’m writing this now from my third-floor hotel room, looking out over Washington Ave., in Minneapolis.

Emphasis not on Minneapolis, although it’s nice to be out of Indiana for a bit, or AWP, although that’s certainly the reason I’m here, or third-floor, even though it gives a bit of a view. No, emphasis on my.

When I was sixteen, my ever-indulgent parents got me a retreat for Christmas. Nothing extravagant, because I didn’t need extravagance; it was just five days at the Super 8 maybe twenty minutes from our house, but for me, with a brand new draft of a novel sitting in front of me, begging to be torn apart and reworked, it was a perfect writerly sanctuary. I stayed in my room with DO NOT DISTURB on the door, blinds drawn, music playing, and manuscript pages and maps and note cards splayed out all around me.

I drank alcohol-free merlot, ate tortillas with pesto, kept my own hours, and hermitted it up (although I think I reached out by text a few times for advice).

I’m not going to hermit in Minneapolis; I’m going to the conference, and to the book fair, and around the city. Still, I have a room, and it’s mine. Not in a permanent way—just in an exclusive one. My little hotel sanctuary.

This evening I took myself and a book to dinner at a restaurant across the street, Sanctuary. I’d read the menu online, and it looked exciting—and it was, but it was also much classier than I anticipated. (Seriously, look at the website. I feel like it was not an unreasonable assumption on my part.) I walked in and was seated by the very well-dressed host … and then looked around and realized that it wasn’t just the host—everyone was very well-dressed.

My first impulse was to apologize profusely—my jeans and Payless shoes and shirt with hops on it had tripped and fallen in here by accident, and I would get out of the way right now. Instead, though, I stayed; I lingered for two hours, over …

garlic, spinach, and parmesan artichoke tartlets, provincal olives, cornichons and a shot of white verjus

liquor 43 bread pudding with salted caramel ice cream and ristretto espresso crème anglaise

a quasi mojo—and absinthe mojito

and a cup of coffee

Not surprisingly, especially to anyone who looked at the menu, it was an expensive linger. Still, it was mine, whether or not I fit in.

Plus, part way through my meal, more conference types started to come in, and writers are a notoriously shabby lot. Suddenly I was not so out of place after all.

Sanctuary takes different forms, see?

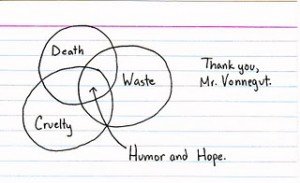

It’s a cliché, the insomniac writer, cursed with consciousness in the lonely, no-man’s-land hours after closing time and before the coffee shops have started their first pots. Maybe their haggard faces are lit by the glow of a computer screen; maybe they’re holding a half-drained bottle of gin in; maybe they’re lying spread-eagled in bed, staring at the ceiling, tired of counting sheep.

It’s a cliché, the insomniac writer, cursed with consciousness in the lonely, no-man’s-land hours after closing time and before the coffee shops have started their first pots. Maybe their haggard faces are lit by the glow of a computer screen; maybe they’re holding a half-drained bottle of gin in; maybe they’re lying spread-eagled in bed, staring at the ceiling, tired of counting sheep.